Photo: RODONG SINMUN/EPA

A collective farm in North Korea; Photo: Clay Gilliand via The Diplomat

After more than a half century of trying to pound the round peg of pastoral agriculture into the square of a mountainous nation, maybe it's time for North Korea's agricultural scientists to rethink. It's perfectly possible to use mountainous terrain to grow crops, and here I'm not talking about making pasture by cutting down trees on mountain slopes, as the North Koreans have done with results that lead to catastrophic flooding because the soil is unable to retain rainwater.

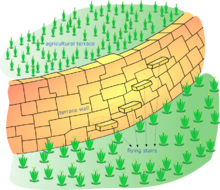

I'm thinking in terms of steppe or terrace farming, as used for more than a thousand years in the South American Andes mountains. Here's an illustration from Wikipedia's all-too-brief article on terrace farming:

Also, the article mentions in passing the use of ziggurats in ancient times in the Middle East for terraced farming although it doesn't provide a citation. Nor is there discussion of this use for ziggurats in Wikipedia's article on such structures, which were mostly assumed to have been built for religious purposes or for taking refuge from a flood. I have always suspected their original use was for terraced farming although I can't offer evidence for this; it was just the first thought that came to my mind about the structures when I first saw photographs of them in my youth.

In any case where flat cropland is at a premium, one can think of terracing, and I can certainly think of how ziggurat architecture can be used for such.

One can also think of the incredible innovations (made possible by cutting-edge science) applied to the ancient method called silvo-pasturing. The genius idea of modern silvo- pasturing, which greatly reduces the acreage needed for grazing land by stacking forage rather than spreading them out for the cows' consumption, can be applied to raising crops for human consumption.

This is already being done with coffee trees and plantains. In other words, plant scientists can figure out what kind of food/beverage crop could raised on top of another crop. Or it could be a combo -- one plant in the stack would be, say, legumes for human consumption, and another plant in the stack for animal feed.

The trick is that the plant on top is leafy enough to allow the one below to get enough sunlight, or that the one below is shade loving; figuring all this out is where the cutting-edge science comes in.

As for water, science based silvo-pasturing, which can produce the same amount of dairy, meat, and timber in half the land area, requires almost no fertilizer -- or irrigation. And that's even during dry atmospheric conditions. Yes, you read that right.

This type of agriculture is old news to readers who've been with this blog for years; for people chary of clicking on links to unknown sources the report I link to above is at Yale Environment 360, which is associated with Yale University. The report, by Lisa Palmer, was published in March 2014 under the title In the Pastures of Colombia, Cows, Crops and Timber Coexist: "As an ambitious program in Colombia demonstrates, combining grazing and agriculture with tree cultivation can coax more food from each acre, boost farmers’ incomes, restore degraded landscapes, and make farmland more resilient to climate change."

There are also a great many things the North Koreans could be doing in terms of preserving food and conserving water, and which, again, relate to newer approaches and methods.

See the Christian Science Monitor's great "Search for Solutions" series, three of which I've posted here in recent days.

As to the immediate drought crisis in North Korea and the specter of another famine, below are three news reports -- two recent and one, the most interesting, published in 2016 -- and analyses by two experts on DPRK; between them they cover all the bases in terms of conventional policy advice. Their observations are as relevant today as when they were published in 2015, during the last drought crisis in DPRK.

July 24, 2017

I'm thinking in terms of steppe or terrace farming, as used for more than a thousand years in the South American Andes mountains. Here's an illustration from Wikipedia's all-too-brief article on terrace farming:

Also, the article mentions in passing the use of ziggurats in ancient times in the Middle East for terraced farming although it doesn't provide a citation. Nor is there discussion of this use for ziggurats in Wikipedia's article on such structures, which were mostly assumed to have been built for religious purposes or for taking refuge from a flood. I have always suspected their original use was for terraced farming although I can't offer evidence for this; it was just the first thought that came to my mind about the structures when I first saw photographs of them in my youth.

In any case where flat cropland is at a premium, one can think of terracing, and I can certainly think of how ziggurat architecture can be used for such.

One can also think of the incredible innovations (made possible by cutting-edge science) applied to the ancient method called silvo-pasturing. The genius idea of modern silvo- pasturing, which greatly reduces the acreage needed for grazing land by stacking forage rather than spreading them out for the cows' consumption, can be applied to raising crops for human consumption.

This is already being done with coffee trees and plantains. In other words, plant scientists can figure out what kind of food/beverage crop could raised on top of another crop. Or it could be a combo -- one plant in the stack would be, say, legumes for human consumption, and another plant in the stack for animal feed.

The trick is that the plant on top is leafy enough to allow the one below to get enough sunlight, or that the one below is shade loving; figuring all this out is where the cutting-edge science comes in.

As for water, science based silvo-pasturing, which can produce the same amount of dairy, meat, and timber in half the land area, requires almost no fertilizer -- or irrigation. And that's even during dry atmospheric conditions. Yes, you read that right.

This type of agriculture is old news to readers who've been with this blog for years; for people chary of clicking on links to unknown sources the report I link to above is at Yale Environment 360, which is associated with Yale University. The report, by Lisa Palmer, was published in March 2014 under the title In the Pastures of Colombia, Cows, Crops and Timber Coexist: "As an ambitious program in Colombia demonstrates, combining grazing and agriculture with tree cultivation can coax more food from each acre, boost farmers’ incomes, restore degraded landscapes, and make farmland more resilient to climate change."

There are also a great many things the North Koreans could be doing in terms of preserving food and conserving water, and which, again, relate to newer approaches and methods.

See the Christian Science Monitor's great "Search for Solutions" series, three of which I've posted here in recent days.

As to the immediate drought crisis in North Korea and the specter of another famine, below are three news reports -- two recent and one, the most interesting, published in 2016 -- and analyses by two experts on DPRK; between them they cover all the bases in terms of conventional policy advice. Their observations are as relevant today as when they were published in 2015, during the last drought crisis in DPRK.

July 24, 2017

North Korean drought leaves Kim's kingdom crippled amid deadly food crisis, UN warns

By Thomas Hunt

Sunday Express (U.K.)

NORTH Korea faces a devastating drought that threatens a food crisis in the sanction–hit country, a United Nations report has warned.

The secretive state was previously ravaged by a widespread famine where at least 2 million people are estimated to have died between 1995 and 1999.

The UN Food Agriculture Organisation [FAO] said: “More rains are urgently needed to avoid significant decreases in the main 2017 cereal production season.

“Should drought conditions persist, the food security situation is likely to further deteriorate.”

he UN agency estimated North Korea’s early-season crop production was down 30 per cent to 310,000 tonnes from the same time period last year.

Vincent Martin, FAO representative in China and North Korea, said in a statement: “Seasonal rainfall in main cereal producing areas have been below the level of 2001, when cereal production dropped to the unprecedented level of only two million tonnes.”

A persistent lack of rainfall in North Korea in recent months has decimated staple crops such as rice, maize, potatoes and soybean, which many of the country's citizens depend on during the lean season that stretches from May to September.

Jean Lee, global fellow at Wilson Centre, said: “There's a chronic shortfall of food… In terms of being able to feed their people, they never recovered.

“Then on top of the drought, they may get some monsoon flooding when it does start to rain. So this country that has very little arable land, 85 per cent mountains [has a] vicious cycle of drought and flooding.”

Inefficient food production means that large parts of the North Korean population face malnutrition or death.

The FAO said in a statement: “Increased food imports, commercial and/or through food aid, would be required during the next three lean months [July to September] until the harvest of the 2017 main season from the end of September to October, in order to ensure adequate food consumption for the most vulnerable people.”

Kim continues to flex his state’s military muscle after the belligerent North tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) it claimed is capable of hitting Hawaii, located in the Pacific ocean.

The drought follows calls from an Obama era Envoy for the hermit kingdom to be handed humanitarian aid by the US.

The astonishing claim did come with a caveat, that the aid should only be given to the residents if transparency of distribution is secured.

Earlier this month former-envoy Robert King said: “Aid at the civic level should also be extended to the North under the same condition.”

By Thomas Hunt

Sunday Express (U.K.)

NORTH Korea faces a devastating drought that threatens a food crisis in the sanction–hit country, a United Nations report has warned.

The secretive state was previously ravaged by a widespread famine where at least 2 million people are estimated to have died between 1995 and 1999.

The UN Food Agriculture Organisation [FAO] said: “More rains are urgently needed to avoid significant decreases in the main 2017 cereal production season.

“Should drought conditions persist, the food security situation is likely to further deteriorate.”

he UN agency estimated North Korea’s early-season crop production was down 30 per cent to 310,000 tonnes from the same time period last year.

Vincent Martin, FAO representative in China and North Korea, said in a statement: “Seasonal rainfall in main cereal producing areas have been below the level of 2001, when cereal production dropped to the unprecedented level of only two million tonnes.”

A persistent lack of rainfall in North Korea in recent months has decimated staple crops such as rice, maize, potatoes and soybean, which many of the country's citizens depend on during the lean season that stretches from May to September.

Jean Lee, global fellow at Wilson Centre, said: “There's a chronic shortfall of food… In terms of being able to feed their people, they never recovered.

“Then on top of the drought, they may get some monsoon flooding when it does start to rain. So this country that has very little arable land, 85 per cent mountains [has a] vicious cycle of drought and flooding.”

Inefficient food production means that large parts of the North Korean population face malnutrition or death.

The FAO said in a statement: “Increased food imports, commercial and/or through food aid, would be required during the next three lean months [July to September] until the harvest of the 2017 main season from the end of September to October, in order to ensure adequate food consumption for the most vulnerable people.”

Kim continues to flex his state’s military muscle after the belligerent North tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) it claimed is capable of hitting Hawaii, located in the Pacific ocean.

The drought follows calls from an Obama era Envoy for the hermit kingdom to be handed humanitarian aid by the US.

The astonishing claim did come with a caveat, that the aid should only be given to the residents if transparency of distribution is secured.

Earlier this month former-envoy Robert King said: “Aid at the civic level should also be extended to the North under the same condition.”

[END REPORT]

By Joseph Hicks

TIME

The worst North Korean drought since 2001 has severely damaged staple crop production and could lead to serious food shortages, according to a new report from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The FOA report, an early warning alert published Thursday, warns that a drop in bilateral food aid to North Korea — in part a result of sanctions imposed in response to the hermetic nation's nuclear weapons program — has made the country especially vulnerable to famine.

Prolonged dry weather during the crucial period from April to late June is likely to cause a significant decrease in this year's harvest, the report said. North Korea now requires "immediate interventions" such as food imports and agricultural assistance to make up for the shortfall.

"Seasonal rainfall in main cereal producing areas have been below the level of 2001, when cereal production dropped to the unprecedented level of only two million tonnes, causing a sharp deterioration in food security conditions of a large part of the population," said Vincent Martin, an FAO representative in China and North Korea, in a press release that accompanied the report.

Staple crops such as rice, maize, potatoes and soybean — which many North Koreans traditionally rely on to get through the May to September lean season — had been decimated by the drought. Vulnerable people such as children and the elderly would be worst affected by food insecurity, the FAO said.

Hundreds of thousands of North Koreans are believed to have died during widespread famine in the 1990's.

By Julian Ryall

The Telegraph (U.K.)

In a proclamation that will strike fear into the hearts of the North Korean people, state media has ordered the citizenry to prepare for a new "arduous march".

The term was first coined by the North Korean leadership in 1993 as a metaphor for the four-year famine that decimated the nation from 1994 [to 1999].

The famine - in which as many as 3.5 million of the nation's 22 million people died - was brought on by economic mismanagement, natural disasters, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the consequent loss of aid, combined with the regime's insistence on continuing a life of luxury and feeding the military.

Now, less than one month after the United Nations Security Council voted in favour of new sanctions against North Korea for its recent nuclear and missile tests, Pyongyang has announced a nationwide campaign to save food.

"The road to revolution is long and arduous", an editorial in the state-run Rodong Sinmun newspaper stated on Monday. "We may have to go on an arduous march, during which we will have to chew the roots of plants once again".

The Chosun Ilbo, a South Korean newspaper, reported that every citizen of Pyongyang is being ordered to provide 1kg (2.2lb) of rice to the state's warehouses every month, while farmers are being forced to "donate" additional supplies from their own meagre crops to the military.

There are also reports of North Koreans hoarding food supplies due to fears of another famine, while the regime has started to crack down on the open-air markets that serve as an important source of additional food for city-dwellers and have been tolerated in recent years.

The markets began to appear after an attempt in 2009 to reform the North's currency went awry, causing the national food-rationing system to collapse and triggering fears of another famine.

The Rodong Sinmun also warned that despite the hardships, allegiances to Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, would not be permitted to waver.

"Even if we give up our lives, we should continue to show our loyalty to our leader, Kim Jong-un, until the end of our lives", the newspaper said, demanding a "70-day campaign of loyalty".

North Korea has requested 440,000 tons of food aid from overseas to feed its people this year, although a mere 17,600 tons had been delivered by early February.

Such is the dire situation that scientists have found that migrating vultures are feasting before attempting to cross the country because they know it has slim pickings.

[END REPORT]

The Telegraph (U.K.)

In a proclamation that will strike fear into the hearts of the North Korean people, state media has ordered the citizenry to prepare for a new "arduous march".

The term was first coined by the North Korean leadership in 1993 as a metaphor for the four-year famine that decimated the nation from 1994 [to 1999].

The famine - in which as many as 3.5 million of the nation's 22 million people died - was brought on by economic mismanagement, natural disasters, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the consequent loss of aid, combined with the regime's insistence on continuing a life of luxury and feeding the military.

Now, less than one month after the United Nations Security Council voted in favour of new sanctions against North Korea for its recent nuclear and missile tests, Pyongyang has announced a nationwide campaign to save food.

"The road to revolution is long and arduous", an editorial in the state-run Rodong Sinmun newspaper stated on Monday. "We may have to go on an arduous march, during which we will have to chew the roots of plants once again".

The Chosun Ilbo, a South Korean newspaper, reported that every citizen of Pyongyang is being ordered to provide 1kg (2.2lb) of rice to the state's warehouses every month, while farmers are being forced to "donate" additional supplies from their own meagre crops to the military.

There are also reports of North Koreans hoarding food supplies due to fears of another famine, while the regime has started to crack down on the open-air markets that serve as an important source of additional food for city-dwellers and have been tolerated in recent years.

The markets began to appear after an attempt in 2009 to reform the North's currency went awry, causing the national food-rationing system to collapse and triggering fears of another famine.

The Rodong Sinmun also warned that despite the hardships, allegiances to Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, would not be permitted to waver.

"Even if we give up our lives, we should continue to show our loyalty to our leader, Kim Jong-un, until the end of our lives", the newspaper said, demanding a "70-day campaign of loyalty".

North Korea has requested 440,000 tons of food aid from overseas to feed its people this year, although a mere 17,600 tons had been delivered by early February.

Such is the dire situation that scientists have found that migrating vultures are feasting before attempting to cross the country because they know it has slim pickings.

[END REPORT]

By Andrei Lankov

Foreign Policy

[Andrei Lankov is a Director at (nonprofit) NK News and writes exclusively for the site as one of the world's leading authorities on North Korea. A graduate of Leningrad State University, he attended Pyongyang's Kim Il Sung University from 1984-5 - an experience you can read about here. In addition to his writing, he is also a Professor at Kookmin University (Seoul, South Korea). - From NK News website]

North Korea is experiencing a major drought. The first news about grave water shortages appeared earlier this year; in late May, the United Nations warned that the country might face a “huge food deficit.” By mid-June, the North Korean drought had become an international news story. And on June 16, the Korean Central News Agency, the North Korean official wire service, finally chimed in, calling it “the worst drought in 100 years.”

When people talk today about problems in North Korean agriculture, the grim events of the late 1990s loom. Back then, over half a million people starved to death as society broke down following the passing of the country’s longtime leader Kim Il Sung — the worst famine East Asia had seen in decades. So, unsurprisingly, international media tends to worry about a major famine.

It is too early to estimate the scale of the problem. North Korea is one of the world’s most opaque countries: Foreign journalists see only what their handlers allow them to see and hear from the locals only what the authorities order the locals to tell. Problems can be greatly exaggerated, or hidden — whichever better serves the current demands of Pyongyang.

Nonetheless, there is no need to be alarmist. Indeed, as every North Korean watcher with a sufficiently long memory will tell you, official stories of drought and other natural disasters have been a common feature in North Korean propaganda for decades. For example, KCNA reported floods in 2006, 2007, and 2012, and drought in 2012 and 2014. And this, in turn, led to Western news media reporting on the subject. For example, “Korean Drought Worst in a Century for North and South Korea” and “North Korea Suffering Serious Drought” are two AP headlines from mid-2012; in 2007, the Guardian headlined a story titled “Flooding Devastates North Korea.” And in spring 2014, there was the Reuters headline, “North Korea Faces Worst Drought in Over a Decade.”

Why does Pyongyang do it? And are these calamitous events actually happening?

In the depths of the famine in the late 1990s, North Korean media managers learned that if Pyongyang is going to ask for foreign food assistance, it must first admit it has serious problems with food production. Back then, that move was a dramatic break with the past. In previous decades, the North Koreans, in their encounters with foreigners, were required to paint a picture of nearly perfect paradise, where nothing could possibly go wrong.

When people talk today about problems in North Korean agriculture, the grim events of the late 1990s loom. Back then, over half a million people starved to death as society broke down following the passing of the country’s longtime leader Kim Il Sung — the worst famine East Asia had seen in decades. So, unsurprisingly, international media tends to worry about a major famine.

It is too early to estimate the scale of the problem. North Korea is one of the world’s most opaque countries: Foreign journalists see only what their handlers allow them to see and hear from the locals only what the authorities order the locals to tell. Problems can be greatly exaggerated, or hidden — whichever better serves the current demands of Pyongyang.

Nonetheless, there is no need to be alarmist. Indeed, as every North Korean watcher with a sufficiently long memory will tell you, official stories of drought and other natural disasters have been a common feature in North Korean propaganda for decades. For example, KCNA reported floods in 2006, 2007, and 2012, and drought in 2012 and 2014. And this, in turn, led to Western news media reporting on the subject. For example, “Korean Drought Worst in a Century for North and South Korea” and “North Korea Suffering Serious Drought” are two AP headlines from mid-2012; in 2007, the Guardian headlined a story titled “Flooding Devastates North Korea.” And in spring 2014, there was the Reuters headline, “North Korea Faces Worst Drought in Over a Decade.”

Why does Pyongyang do it? And are these calamitous events actually happening?

In the depths of the famine in the late 1990s, North Korean media managers learned that if Pyongyang is going to ask for foreign food assistance, it must first admit it has serious problems with food production. Back then, that move was a dramatic break with the past. In previous decades, the North Koreans, in their encounters with foreigners, were required to paint a picture of nearly perfect paradise, where nothing could possibly go wrong.

Those times have passed: The 1990s famine taught the North Koreans that they could not beg for foreign aid while also boasting about unprecedented economic successes. That’s not to say the North Korean media is remotely transparent about these events. They tend to remain silent on the human casualties or imply that nobody was killed. The truth of what actually happened with the natural disasters — like so much in North Korea — is often impossible to know.

Which returns us to the present. Pyongyang’s recent decision to report the drought implies that it probably at least considered a request for foreign aid.Indeed, the visitors’ reports make one suspect that this time the scale of the problems is great. European aid experts who recently visited the country described to me the sight of soldiers and elementary school children mobilized to water vegetable gardens with buckets and frequent blackouts, even in buildings which previously had a reliable electricity supply.

Nonetheless, this does not mean that we should ready ourselves for a rerun of the 1996-1999 famine. Things are different nowadays.

Which returns us to the present. Pyongyang’s recent decision to report the drought implies that it probably at least considered a request for foreign aid.Indeed, the visitors’ reports make one suspect that this time the scale of the problems is great. European aid experts who recently visited the country described to me the sight of soldiers and elementary school children mobilized to water vegetable gardens with buckets and frequent blackouts, even in buildings which previously had a reliable electricity supply.

Nonetheless, this does not mean that we should ready ourselves for a rerun of the 1996-1999 famine. Things are different nowadays.

First, North Korean agriculture has steadily recovered over the last decade, especially under Kim Jong Un, who took power in December 2011 following the death of his father, Kim Jong Il. Despite the spring 2014 drought, the 2013 and 2014 harvests were the best in decades: In those two years — and for the first time since the late 1980s — North Korea came very close to food self-sufficiency. According to estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the country annually produced roughly 5.3 million metric tons of cereal in 2013 and 2014. During the famine, annual harvest was below 3 million metric tons.

What caused that success? North Korea’s move toward its own version of the Household Responsibility System, a farming system China introduced in the late 1970s at the early stages of its economic reforms, deserves some of that credit. Starting in roughly 2013, Pyongyang allowed farmers to register their family as a production unit — thereby keeping up proper ideological appearances of “socialist agriculture” — and allowed them to toil the same area every year, with 30 percent of the harvest as a reward. North Korean farmers ceased to be serfs working for fixed rations and became sharecroppers, whose well-being depends on the productivity of their labor. The change produced wonderful results, and North Korean agricultural recovery sped up significantly.

That new system worked well during the 2014 drought and will likely continue to be successful during the 2015 drought, which appears more severe. The 2015 harvest will likely drop — but it is unlikely to approach the level of the disastrous 1990s.

Nonetheless, even a small decline of the harvest is dangerous, since 5.2 million tons is, essentially, a subsistence level for North Korea’s roughly 25 million people. If the harvest drops, it means starvation, albeit on a relatively limited scale.

However, Pyongyang knows how to handle such issues. Gone are the times when officials were afraid to admit any problems out of fear that such admission would make them vulnerable domestically to accusations of treason. North Koreans now know how to ask for aid, and the recent KCNA reports about the drought were the first step in the right direction.

What caused that success? North Korea’s move toward its own version of the Household Responsibility System, a farming system China introduced in the late 1970s at the early stages of its economic reforms, deserves some of that credit. Starting in roughly 2013, Pyongyang allowed farmers to register their family as a production unit — thereby keeping up proper ideological appearances of “socialist agriculture” — and allowed them to toil the same area every year, with 30 percent of the harvest as a reward. North Korean farmers ceased to be serfs working for fixed rations and became sharecroppers, whose well-being depends on the productivity of their labor. The change produced wonderful results, and North Korean agricultural recovery sped up significantly.

That new system worked well during the 2014 drought and will likely continue to be successful during the 2015 drought, which appears more severe. The 2015 harvest will likely drop — but it is unlikely to approach the level of the disastrous 1990s.

Nonetheless, even a small decline of the harvest is dangerous, since 5.2 million tons is, essentially, a subsistence level for North Korea’s roughly 25 million people. If the harvest drops, it means starvation, albeit on a relatively limited scale.

However, Pyongyang knows how to handle such issues. Gone are the times when officials were afraid to admit any problems out of fear that such admission would make them vulnerable domestically to accusations of treason. North Koreans now know how to ask for aid, and the recent KCNA reports about the drought were the first step in the right direction.

China, whose relations with North Korea have recently been tense, has already expressed its willingness to help. Other countries are likely to follow, perhaps through the United Nations, which has been trying to fundraise $137 million for North Korean aid in 2015 — as of early June, it remains roughly $62 million short. If necessary, government minders could escort foreign visitors to the famine-stricken areas — like they did in 2012 and 2013 — and show them starving children and dead dry fields.

There might be some hopes in the United States that a looming famine will make Pyongyang more ready to negotiate on the nuclear issue. This is an illusion. First, for the reasons described above, a famine is unlikely. Second, even a famine may have little, if any, impact on North Korean decision-makers. Through the truly massive famine of the 1990s, they did not slow down their nuclear project and continued to spend money on it — roughly estimated at $3 billion over the last few decades.

Now, when the nuclear program is much less burdensome and when the country’s food problems are much less severe, they have even less reason to negotiate. The North Korean elite believe that nuclear weapons guarantee their survival, and they are not going to surrender the nukes in order to improve the life of farmers in remote villages — famine or otherwise.

[END ANALYSIS]

This year, both North Korean authorities and international agencies and experts have once again spoken of a drought, the worst in one hundred years according to the North Korean government news outlet. UNICEF, the UN agency for children, has already reported that North Korean children are suffering from an increased prevalence of diarrhea associated with a lack of safe drinking water.

It’s business as usual, in other words. The alarm bells of North Korean food shortages and natural disasters are a yearly phenomenon with the same regularity as Christmas. In the summer of 2007, the country was hit by some of the worst floods in its modern history, which saw 200,000 people displaced and at least hundreds killed. Floods devastated the country again both in 2012 and 2013, albeit on a smaller magnitude. And as recently as June last year, just like this year, North Korea reported that it was facing a drought – then the worst in a decade.

This recurring state of emergency is by no means inevitable. North Korea’s inability to cope with natural disasters, and to feed its own population, is a direct result of deliberate government policies. Even after the devastating famine in the 1990s, when hundreds of thousands of its citizens starved to death as the economy collapsed, North Korea refused to abandon its socialist foundations and economic planning.

Foreign aid has been an integral part of North Korea’s food supply planning since the mid-1990s. This year is no exception, and the international community may have to allocate additional funds to North Korean food aid in order to prevent widespread malnutrition. But aid won’t change anything in the long run. North Korea will continue to be highly vulnerable to simple weather changes, unless its most basic economic policies are completely overhauled.Sadly, in trying to counter North Korea’s suffering, the international community may ironically be contributing to its prolonging. The United Nations and other donors are enabling the North Korean regime to continue its disastrous policies when they act as cushions whenever the country runs out of food.

The most fundamental of these policies is that of economic autarky. Countries with well-functioning economic systems that allow for economic specialization and trade would simply see food imports increase to offset dryer weather conditions. This cannot happen in North Korea. The regime has made efforts from time to time to modernize its system and attract foreign investments, but it has not taken any of the necessary steps to seek integration into the global economy.

The North Korean regime often emphasizes that the country consists mostly of mountainous regions not suitable for farming. That is clearly true, but the logical response to such a challenge would be to seek to import agricultural goods and export those that the country can produce in greater abundance to a cheaper price than others. Instead, the regime continues to uphold economic and political self-reliance as its overarching goal. More detailed policies have also contributed to the dire situation: For decades, North Koreans have systematically been cutting down trees on mountain slopes to create more farmland, contributing to flooding since the soil has been unable to retain rainwater.

To be sure, some economic and agricultural policy reforms have occurred. Unlike in the country’s more orthodox socialist days, private markets are now tolerated. Many even became formalized and integrated into the economic system after the famine of the 1990s, when the government could no longer restrict them as the socialist distribution system ceased to function.

Under the leadership of Kim Jong-un, some experiments have been made in allowing farmers to keep more of their harvests for private trade and consumption. A large number of special economic zones have been designated by the government and allowed significant freedom to operate and craft their own rules.

These are only a few examples of how the state is trying to get the economy going. But these measures amount to nothing more than tweaking the edges of a failed system. The state still owns all essential means of production. While some scholars have argued that the country’s agricultural reforms have led harvests to increase, the slightly larger harvests of recent years merely seem to be a continuation of a trend that started long before reforms were implemented.

On the contrary, North Korea is not only refusing to change its economic structures to make them more resilient to events like the current drought. The state also continues to suppress those economic mechanisms that could help counter the effects of natural disasters. Even though private legal markets are now part of the formal economy to a large extent, imports and exports are still heavily restricted and largely rely on the willingness of border guards to accept bribes.

While Kim Jong-un has implemented measures that carry the shape of economic liberalization with one hand, his other hand has been used to tighten controls on border trade and smuggling. The government would only need to cease some of its control of the markets to alleviate the food shortages that will likely follow the current drought, a virtually costless measure. So far, it has done nothing of this sort.

Like most disasters often termed as “natural,” the consequences of North Korea’s drought are first and foremost failures of policy, not of nature. By agreeing to supply North Korea’s shortfall in food production, year after year, even as the regime refuses to make any fundamental changes to the system that keeps on failing, the international community acts as an enabler for the regime’s continuing mismanagement.

There might be some hopes in the United States that a looming famine will make Pyongyang more ready to negotiate on the nuclear issue. This is an illusion. First, for the reasons described above, a famine is unlikely. Second, even a famine may have little, if any, impact on North Korean decision-makers. Through the truly massive famine of the 1990s, they did not slow down their nuclear project and continued to spend money on it — roughly estimated at $3 billion over the last few decades.

Now, when the nuclear program is much less burdensome and when the country’s food problems are much less severe, they have even less reason to negotiate. The North Korean elite believe that nuclear weapons guarantee their survival, and they are not going to surrender the nukes in order to improve the life of farmers in remote villages — famine or otherwise.

[END ANALYSIS]

The Diplomat

Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein is a non-resident Kelly Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS and a fellow at the Stockholm Free World Forum. He writes frequently on North Korean affairs and formerly worked as a special advisor to the Swedish Minister for International Development Cooperation.

By trying to help, the international community may be making long-run matters worse.

It’s business as usual, in other words. The alarm bells of North Korean food shortages and natural disasters are a yearly phenomenon with the same regularity as Christmas. In the summer of 2007, the country was hit by some of the worst floods in its modern history, which saw 200,000 people displaced and at least hundreds killed. Floods devastated the country again both in 2012 and 2013, albeit on a smaller magnitude. And as recently as June last year, just like this year, North Korea reported that it was facing a drought – then the worst in a decade.

This recurring state of emergency is by no means inevitable. North Korea’s inability to cope with natural disasters, and to feed its own population, is a direct result of deliberate government policies. Even after the devastating famine in the 1990s, when hundreds of thousands of its citizens starved to death as the economy collapsed, North Korea refused to abandon its socialist foundations and economic planning.

Foreign aid has been an integral part of North Korea’s food supply planning since the mid-1990s. This year is no exception, and the international community may have to allocate additional funds to North Korean food aid in order to prevent widespread malnutrition. But aid won’t change anything in the long run. North Korea will continue to be highly vulnerable to simple weather changes, unless its most basic economic policies are completely overhauled.Sadly, in trying to counter North Korea’s suffering, the international community may ironically be contributing to its prolonging. The United Nations and other donors are enabling the North Korean regime to continue its disastrous policies when they act as cushions whenever the country runs out of food.

The most fundamental of these policies is that of economic autarky. Countries with well-functioning economic systems that allow for economic specialization and trade would simply see food imports increase to offset dryer weather conditions. This cannot happen in North Korea. The regime has made efforts from time to time to modernize its system and attract foreign investments, but it has not taken any of the necessary steps to seek integration into the global economy.

The North Korean regime often emphasizes that the country consists mostly of mountainous regions not suitable for farming. That is clearly true, but the logical response to such a challenge would be to seek to import agricultural goods and export those that the country can produce in greater abundance to a cheaper price than others. Instead, the regime continues to uphold economic and political self-reliance as its overarching goal. More detailed policies have also contributed to the dire situation: For decades, North Koreans have systematically been cutting down trees on mountain slopes to create more farmland, contributing to flooding since the soil has been unable to retain rainwater.

To be sure, some economic and agricultural policy reforms have occurred. Unlike in the country’s more orthodox socialist days, private markets are now tolerated. Many even became formalized and integrated into the economic system after the famine of the 1990s, when the government could no longer restrict them as the socialist distribution system ceased to function.

Under the leadership of Kim Jong-un, some experiments have been made in allowing farmers to keep more of their harvests for private trade and consumption. A large number of special economic zones have been designated by the government and allowed significant freedom to operate and craft their own rules.

These are only a few examples of how the state is trying to get the economy going. But these measures amount to nothing more than tweaking the edges of a failed system. The state still owns all essential means of production. While some scholars have argued that the country’s agricultural reforms have led harvests to increase, the slightly larger harvests of recent years merely seem to be a continuation of a trend that started long before reforms were implemented.

On the contrary, North Korea is not only refusing to change its economic structures to make them more resilient to events like the current drought. The state also continues to suppress those economic mechanisms that could help counter the effects of natural disasters. Even though private legal markets are now part of the formal economy to a large extent, imports and exports are still heavily restricted and largely rely on the willingness of border guards to accept bribes.

While Kim Jong-un has implemented measures that carry the shape of economic liberalization with one hand, his other hand has been used to tighten controls on border trade and smuggling. The government would only need to cease some of its control of the markets to alleviate the food shortages that will likely follow the current drought, a virtually costless measure. So far, it has done nothing of this sort.

Like most disasters often termed as “natural,” the consequences of North Korea’s drought are first and foremost failures of policy, not of nature. By agreeing to supply North Korea’s shortfall in food production, year after year, even as the regime refuses to make any fundamental changes to the system that keeps on failing, the international community acts as an enabler for the regime’s continuing mismanagement.

Humanitarian aid is given with the best of intentions, but in the long run, by helping the North Korean regime avoid necessary policy choices, it may be harming rather than helping the North Korean population.

[END ANALYSIS]

********

********

No comments:

Post a Comment