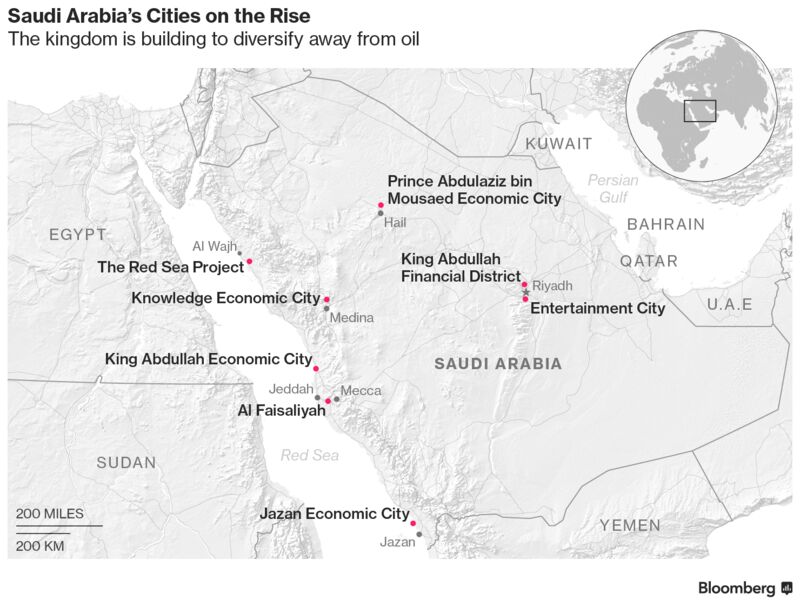

"In the past month alone, the world’s biggest oil exporter has announced two major developments -- one covering an area bigger than Belgium and another almost the size of Moscow. That’s on top of plans to build a series of so-called economic cities -- special zones in logistics, tourism, industry and finance, an entertainment city and a $10 billion financial district."

As to what the Saudis are going to do for water for the new cities, thereby hangs a very salty tale:

2015 - The Other Liquid Gold: Nuclear Power and Desalination in Saudi Arabia; Foreign Affairs:

... Saudi Arabia is a desert country with no permanent rivers or lakes and erratic rainfall. The vast majority of its territory—95 percent—is covered by one of three deserts: the Rub al-Khali, an-Nafud, or ad-Dahna. Most of Saudi Arabia’s natural reservoirs, such as the Saq-Ram and Wajid aquifer systems, are nearly tapped out. Although other promising reservoirs have been found—for example, the Wasia aquifer, which is thought to hold as much water as the entire Persian Gulf—they are nestled deep in the desert, away from urban areas. Tapping into their full potential would take many years and billions of dollars.

As to what the Saudis are going to do for water for the new cities, thereby hangs a very salty tale:

2015 - The Other Liquid Gold: Nuclear Power and Desalination in Saudi Arabia; Foreign Affairs:

... Saudi Arabia is a desert country with no permanent rivers or lakes and erratic rainfall. The vast majority of its territory—95 percent—is covered by one of three deserts: the Rub al-Khali, an-Nafud, or ad-Dahna. Most of Saudi Arabia’s natural reservoirs, such as the Saq-Ram and Wajid aquifer systems, are nearly tapped out. Although other promising reservoirs have been found—for example, the Wasia aquifer, which is thought to hold as much water as the entire Persian Gulf—they are nestled deep in the desert, away from urban areas. Tapping into their full potential would take many years and billions of dollars.

Accordingly, the Kingdom has turned to an obvious solution: desalinated water from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. According to the latest estimates, the country consumes an estimated 3.3 million cubed meters of desalinated water per day, and desalination provides 70 percent of urban water supplies.

Taking salt out of water is an energy-intensive process. It uses about 15,000 kilowatt-hours of power for every million gallons of fresh water produced. As the world’s second-largest oil producer, Saudi Arabia can afford the energy outlay. It already burns approximately 1.5 million barrels of crude oil equivalent every day, with a significant portion of that output powering desalination plants. But oil-powered desalinization plants are not sustainable. Oil reserves will dry up eventually; Saudi Arabia’s thirst will continue.

[...]

*****

2016 - Peak salt: is the desalination dream over for the Gulf states?; Stephen Leahy and Katherine Purvis, The Guardian

The Middle East is home to 70% of the world’s desalination plants, but the more water they process, the less economically viable they become

But Gulf states are heading for “peak salt”: the more they desalinate, the more concentrated wastewater, brine, is pumped back into the sea; and as the Gulf becomes saltier, desalination becomes more expensive.

“In time, it’s going to become impossible to use desalination in a way that makes economic sense,” says Gökçe Günel, an anthropologist at the University of Arizona. “The water will become so saline that it will be too expensive to desalinate.”

The Middle East is home to 70% of the world’s desalination plants – mostly in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Bahrain. Tens of billions of dollars, $24.3bn (£18.8bn) in Saudi Arabia alone, are being invested over the next few years to expand desalination capacity.

The process is cost and energy intensive; it pumps seawater through special filters or boils it to remove the salts. The resulting brine can be nearly twice as salty as normal Gulf waters, according to John Burt, a biologist at New York University Abu Dhabi.

But the 250,000 sq km Gulf is more like a salt-water lake than a sea. It’s shallow, just 35 metres deep on average, and is almost entirely enclosed. The few rivers that feed the Gulf have been dammed or diverted and the region’s hot and dry climate results in high rates of evaporation. Add in a daily dose of around 70m cubic metres of super-salty wastewater from dozens of desalination plants, and it’s not surprising that the water in the Gulf is 25% saltier than normal seawater, says Burt, or that parts are becoming too salty to use.

Peak salt, says Günel, mirrors the concept of peak oil, a popular concept in the 1970s used to describe the point in time when the maximum rate of oil extraction had been reached. “Peak salt describes the point at which desalination becomes unfeasible,” she says.

And studies have shown that the Gulf will only get saltier in the future. Raed Bashitialshaaer, a water resources engineer at Sweden’s Lund University, says that the growth of desalination plants in the region is happening far faster than his own 2011 study estimated.

With groundwater sources either exhausted or non-existent and climate change bringing higher temperatures and less rainfall, Gulf states plan to nearly double the amount of desalination by 2030 (doc). This is bad news for marine life and for the cost of producing drinking water – unless something can be done about the brine.

Farid Benyahia, a chemical engineer at Qatar University, believes he has a solution. He recently patented a process that could eliminate the need for brine disposal by nearly 100%. The process uses pure carbon dioxide (emitted during the desalination process by burning fossil fuels for power) and ammonia to turn brine into baking soda and calcium chloride. Whether the process is cost-effective remains to be seen but Benyahia believes it could be, especially if markets are found for large volumes of the end products.

Other efforts are also underway to reduce desalination’s country-sized carbon footprint which globally accounts for 76m tonnes of carbon dioxide per year – nearly equivalent to Romania’s emissions in 2014.

[...]

*****August 6, 2017 - Saudi Arabia Builds Cities in the Sand to Move Beyond Oil; Sarah Algethami, Bloomberg:

After relying on oil to fuel its economy for more than half a century, Saudi Arabia is turning to its other abundant natural resource to take it beyond the oil age -- desert. The kingdom is converting thousands of square kilometers of sand into new cities as it seeks to diversify away from crude, create jobs and boost investment.

In the past month alone, the world’s biggest oil exporter has announced two major developments -- one covering an area bigger than Belgium and another almost the size of Moscow. That’s on top of plans to build a series of so-called economic cities -- special zones in logistics, tourism, industry and finance, an entertainment city and a $10 billion financial district.

“The overall progress with the economic cities has been very slow, even before the collapse of the oil price,” said Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank PJSC. “Since then, the pace of development has moderated even further with a number of projects being placed on hold.”

When “Saudi Vision 2030” was announced last April, the 84-page blueprint said the government would work to “salvage” and “revamp” economic city projects executed over the past decade that “did not realize their potential.”

Here’s a look at some of Saudi Arabia’s most ambitious projects:

[...]

********

No comments:

Post a Comment