So this is a very strange turn of events and worthy of examination.

The mutiny might have started earlier but as near as I can figure it began June 11. On that date the New York Times reported on a version of what transpired during Karzai's dispute with two officials:

KABUL, Afghanistan — Two senior Afghan officials were showing President Hamid Karzai the evidence of the spectacular rocket attack on a nationwide peace conference earlier this month when Mr. Karzai told them that he believed the Taliban were not responsible.The revelations in the Times report about secret negotiations got no attention from the American public. But on June 24, while the nation's attention was fixed on the Afghanistan War because of General Stanley McChrystal's resignation, the Times tried again, expanding on the June 11 report and adding more specifics.

“The president did not show any interest in the evidence — none — he treated it like a piece of dirt,” said Amrullah Saleh, then the director of the Afghan intelligence service.

Mr. Saleh declined to discuss Mr. Karzai’s reasoning in more detail. But a prominent Afghan with knowledge of the meeting, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that Mr. Karzai suggested in the meeting that it might have been the Americans who carried it out.

Minutes after the exchange, Mr. Saleh and the interior minister, Hanif Atmar, resigned — the most dramatic defection from Mr. Karzai’s government since he came to power nine years ago. Mr. Saleh and Mr. Atmar said they quit because Mr. Karzai made clear that he no longer considered them loyal.

But underlying the tensions, according to Mr. Saleh and Afghan and Western officials, was something more profound: That Mr. Karzai had lost faith in the Americans and NATO to prevail in Afghanistan.

For that reason, Mr. Saleh and other officials said, Mr. Karzai has been pressing to strike his own deal with the Taliban and the country’s archrival, Pakistan, the Taliban’s longtime supporter. According to a former senior Afghan official, Mr. Karzai’s maneuverings involve secret negotiations with the Taliban outside the purview of American and NATO officials.

“The president has lost his confidence in the capability of either the coalition or his own government to protect this country,” Mr. Saleh said in an interview at his home. “President Karzai has never announced that NATO will lose, but the way that he does not proudly own the campaign shows that he doesn’t trust it is working.”

People close to the president say he began to lose confidence in the Americans last summer, after national elections in which independent monitors determined that nearly one million ballots had been stolen on Mr. Karzai’s behalf. The rift worsened in December, when President Obama announced that he intended to begin reducing the number of American troops by the summer of 2011.

“Karzai told me that he can’t trust the Americans to fix the situation here,” said a Western diplomat in Kabul, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “He believes they stole his legitimacy during the elections last year. And then they said publicly that they were going to leave.” ...

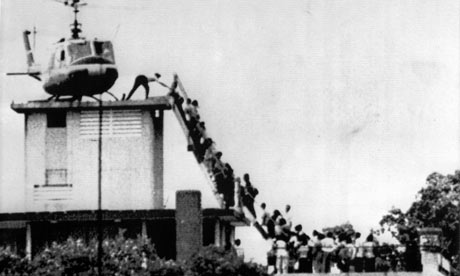

This time, news about the secret negotiations set off an uproar. For readers who missed my post The Last American helicopter out of Kabul, I'll quote again from the Times report titled Pakistan Is Said to Pursue a Foothold in Afghanistan:

...Washington has watched with some nervousness as General Kayani and Pakistan’s spy chief, Lt. Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, shuttle between Islamabad and Kabul, telling Mr. Karzai that they agree with his assessment that the United States cannot win in Afghanistan, and that a postwar Afghanistan should incorporate the Haqqani network, a longtime Pakistani asset. ...State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley, who evidently had not gotten the memo about the mutiny by the time of his June 25 press briefing, only poured fuel on the fire started by the mutineers:

Despite General McChrystal’s 11 visits to General Kayani in Islamabad in the past year, the Pakistanis have not been altogether forthcoming on details of the conversations in the last two months, making the Pakistani moves even more worrisome for the United States, said an American official involved in the administration’s Afghanistan and Pakistan deliberations.

“They know this creates a bigger breach between us and Karzai,” the American official said.

Though encouraged by Washington, the thaw heightens the risk that the United States will find itself cut out of what amounts to a separate peace between the Afghans and Pakistanis, and one that does not necessarily guarantee Washington’s prime objective in the war: denying Al Qaeda a haven. ...

QUESTION: ... the New York Times today reported that the Pakistan army has offered to mediate for peace talks with the Taliban and also with the Haqqani network. Is the offer with you?The White House, more alarmed by the Times mutiny than Crowley's foot-in-mouth replies, scrambled to do damage control. Yesterday Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein and a toady in the GOP camp, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, were packed off to Fox News Cable's Sunday show to give assurances that if General Petraeus needed more time to win the war in Afghanistan he had it.

MR. CROWLEY: Well, as we’ve said many times, this is an Afghan-led process, but obviously there are discussions going on between Afghan officials and Pakistani officials, and we certainly want to see ways in which Pakistan can be supportive of this broader process.

QUESTION: Do you see the Haqqani network coming – sharing power with the Afghan Government? Do you support that?

MR. CROWLEY: We have been very clear in terms of the conditions that any individual or any entity need to meet in order to have a constructive role in Afghanistan’s future: renouncing violence, terminating any ties to al-Qaida, and respecting the Afghan constitution. Anyone who meets those criteria can play a role in Afghan’s future.

Leon Panetta was also dispatched to the Sunday morning TV network circuit, which receives close attention here in the nation's capital. So it came to pass that Panetta made his first appearance on American network television since he became director of the CIA. He appeared on ABC's "This Week" and faced questions from Jake Tapper, who soon turned discussion to the June 24 Times report:

The New York Times reported this week that Pakistani officials say they can deliver the network of Sirajuddin Haqqani, an ally of Al Qaida, who runs a major part of the insurgency into Afghanistan into a power sharing arrangement. In addition, Afghan officials say the Pakistanis are pushing various other proxies with Pakistani General Kayani personally offering to broker a deal with the Taliban leadership. Do you believe Pakistan will be able to push the Haqqani network into peace negotiations?Panetta responded with a broad pantomime to convey that only fools believed what they read in the newspapers then replied:

You know, I read all the same stories, we get intelligence along those lines, but the bottom line is that we really have not seen any firm intelligence that there's a real interest among the Taliban, the militant allies of Al Qaida, Al Qaida itself, the Haqqanis, TTP, other militant groups. We have seen no evidence that they are truly interested in reconciliation, where they would surrender their arms, where they would denounce Al Qaida, where they would really try to become part of that society.But never content to miss a chance to embarrass one of his appointees, President Obama took it upon himself to personally quash the New York Times mutiny. This set up a contradiction between his remarks and Panetta's, which the Times highlighted in their report on the Panetta interview, C.I.A. Chief Sees Taliban Power-Sharing as Unlikely:

We've seen no evidence of that and very frankly, my view is that with regards to reconciliation, unless they're convinced that the United States is going to win and that they're going to be defeated, I think it's very difficult to proceed with a reconciliation that's going to be meaningful.

... While Mr. Obama said a political solution to the conflict was necessary and suggested elements of the Taliban insurgency could be part of negotiations, he said any such effort must be viewed with caution. The C.I.A. director, Leon E. Panetta, was even more forceful in expressing his doubts.I appreciate Mr Panetta's college try. But if he thinks it's difficult to proceed with reconciliation unless the Taliban are convinced that "the United States is going to win and that they’re going to be defeated," how would he explain the efforts of the Obama administration and the NATO command to pressure Karzai to negotiate with Taliban fighters?

“We have seen no evidence that they are truly interested in reconciliation, where they would surrender their arms, where they would denounce Al Qaeda, where they would really try to become part of that society,” Mr. Panetta said on ABC’s “This Week.”

Acknowledging that the American-led counterinsurgency effort was facing unexpected difficulty, Mr. Panetta said that the Taliban and their allies had little motive to contemplate a power-sharing arrangement in Afghanistan.

“We’ve seen no evidence of that and very frankly, my view is that with regards to reconciliation, unless they’re convinced that the United States is going to win and that they’re going to be defeated, I think it’s very difficult to proceed with a reconciliation that’s going to be meaningful,” he said.

Mr. Obama, speaking later after the Group of 20 meeting in Toronto, noted that as the Afghanistan war approached its 10th anniversary, it was the longest foreign war in American history, and that “ultimately as was true in Iraq, so will be true in Afghanistan, we will have to have a political solution.” [Pundita note: Odd. I thought it was a military victory in Iraq that was the solution.]

As for Pakistan’s effort to broker talks, Mr. Obama added: “I think it’s too early to tell. I think we have to view these efforts with skepticism but also with openness. The Taliban is a blend of hard-core ideologues, tribal leaders, kids that basically sign up because it’s the best job available to them. Not all of them are going to be thinking the same way about the Afghan government, about the future of Afghanistan. And so we’re going to have to sort through how these talks take place.”

The president avoided any direct comment on whether the Haqqani network, the Taliban element reportedly proposed by Pakistan as part of a deal, could become part of Afghanistan’s future leadership. But he said that “conversations between the Afghan government and the Pakistani government, building trust between those two governments, are a useful step.”

The comments Sunday were the administration’s first public response to a report of Pakistan’s deal-brokering efforts last week in The New York Times. ...

From a June 25 report for The New York Times titled Karzai Pressed to Move on Luring Low-Level Taliban to Lay Down Arms :

KABUL, Afghanistan — Three weeks after a grand assembly recommended making peace with the Taliban and other armed groups, NATO and Afghan officials are pressing President Hamid Karzai to move more quickly to set up a council to oversee the process and to set in motion a plan to win over low-level Taliban fighters."Afghan political concerns?" Well I guess that's one way of describing Afghans who're so frightened and angry about Karzai's negotiations with the Taliban they're threatening civil war. From a June 26 report for the New York Times titled Overture to Taliban Jolts Afghan Minorities:

Since the closing of the grand peace assembly, or jirga, a committee to review the cases of detainees being held without charge or evidence — another of its recommendations — has already started working and released a number of prisoners.

But a decree to initiate the rest of the program, which is focused on the reintegration of Taliban foot soldiers, has not been signed, Mohammed Massoom Stanekzai, the presidential adviser in charge of the effort, said this week.

The Afghan peace plan envisages winning over low-level fighters and commanders, while negotiating a higher-level political reconciliation with the leaders of the insurgency and conducting diplomacy to gain the support of neighboring countries, such as Pakistan and Iran, which have links to the insurgents.

The plan has moved slowly, however, because of the need to bow to Afghan political concerns, as well as reservations in Washington over making peace with the Taliban leadership. But the plan for reintegration has received American backing.

“If we don’t get it going soon we will start missing the boat,” said Maj. Gen. Philip Jones, who is in charge of the NATO unit that is working on the plan. “We have to catch this moment here in every sense.”

The reintegration plan is nominally an Afghan one, drafted by Mr. Stanekzai, but with the close collaboration of NATO officials since it is seen as a vital part of the coalition counterinsurgency strategy devised by Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal ...

Talks between Mr. Karzai and the Pakistani leaders have been unfolding here and in Islamabad for several weeks, with some discussions involving bestowing legitimacy on Taliban insurgents.I'll interrupt here to ask how Admiral Mullen plans to forbid Afghanistan from tearing apart if Washington and the NATO command keep pushing Karzai to negotiate with the Taliban?

The leaders of these minority communities say that President Karzai appears determined to hand Taliban leaders a share of power — and Pakistan a large degree of influence inside the country. The Americans, desperate to end their involvement here, are helping Mr. Karzai along and shunning the Afghan opposition, they say.

Mr. Oghly said he was disillusioned with the Americans and their NATO allies, who he says appear to be urging Mr. Karzai along. “We are losing faith in our foreign friends,” he said.

Adm. Mike Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said he was worried about “the Tajik-Pashtun divide that has been so strong.” American and NATO leaders, he said, are trying to stifle any return to ethnic violence.

“It has the potential to really tear this country apart,” Admiral Mullen said in an interview. “That’s not what we are going to permit.”

To return to the Times report:

Afghanistan’s minorities — especially the ethnic Tajiks — have always been the most reliable American allies, and made up the bulk of the anti-Taliban army that the Americans aided following the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001.Will President Obama manage to quell the uprising at the New York Times? From their coverage of the Panetta interview, I think the answer from the Times is 'No par-ley!'

The situation is complicated by the politics of the Afghan Army, the centerpiece of American-led efforts to enable the Afghan military to one day take over. The ethnic mix of the Afghan Army is roughly proportional to the population, and the units in the field are mixed themselves. But non-Pashtuns are widely believed to do the bulk of the fighting.

There are growing indications of ethnic fissures inside the army. President Karzai recently decided to remove Bismullah Khan, the chief of staff of the Afghan Army, and make him the interior minister instead. Mr. Khan is an ethnic Tajik, and a former senior leader of the Northern Alliance, the force that fought the Taliban in the years before Sept. 11. Whom Mr. Karzai decides to put in Mr. Khan’s place will be closely watched.

One recent source of tension was the resignation of Amrullah Saleh, the head of Afghan intelligence service and an ethnic Tajik. Mr. Saleh, widely regarded as one of the most competent aides, resigned after Mr. Karzai said he no longer had faith that he could do the job.

Along with Mr. Khan, the army chief of staff, Mr. Saleh was a former aide to Ahmed Shah Massoud, the legendary commander who fought both the Soviet Union and the Taliban. Since leaving the government, Mr. Saleh has started what appears to be the beginning of a political campaign.

Other prominent Afghans have begun to organize along mostly ethnic lines. Abdullah Abdullah, the former foreign minister and presidential candidate, has been hosting gatherings at his farm outside Kabul. In an interview, he said he was preparing to announce the formation of what would amount to an opposition party. Mr. Abdullah, who is of Pashtun and Tajik heritage, said his movement would include Afghans from all the major communities. But his source of power has historically been Afghanistan’s Tajik community.

Mr. Abdullah said he disagreed with the thrust of Mr. Karzai’s policy of engagement with the Taliban and Pakistan. It would be impossible to share power with Taliban leaders, Mr. Abdullah said, because of their support for terrorism and the draconian brand of Islam they would try to impose on everyone else.

“We bring the Taliban into the government — we give them one or two provinces,” Mr. Abdullah said. “If that is what they think, it is not going to happen that way. Anybody thinking in that direction, they are lost. Absolutely lost.”

The trouble, Mr. Abdullah said, is that the Taliban, once given a slice of power, would not be satisfied. “They will take advantage of this,” he said of a political settlement, “and then they will continue.”

The prerequisite for any deal with the Taliban, Afghan and American officials have said repeatedly, is that insurgents renounce their support of terrorists (including Al Qaeda), and that they promise to support the Afghan Constitution.

Beyond that, though, Mr. Karzai’s goals vis-à-vis the Taliban are difficult to discern. Recently he has told senior Afghan officials that he no longer believes that the Americans and NATO can prevail in Afghanistan and that they will probably leave soon. [Pundita note: Reference the June 11 Times report] That fact may make Mr. Karzai more inclined to make a deal with both Pakistan and the Taliban.

As for the Pakistanis, their motives are even more opaque. For years, Pakistani leaders have denied supporting the Taliban, but evidence suggests that they continue to do so. In recent talks, the Pakistanis have offered Mr. Karzai a sort of strategic partnership — and one that involves giving at least one the most brutal Taliban groups, the Haqqani network, a measure of legitimacy in Afghanistan.

Two powerful Pakistani officials — Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the army chief of staff; and Lt. Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, the chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence agency, or ISI, — are set to arrive Monday for talks with Mr. Karzai.

Afghanistan’s non-Pashtun leaders are watching these discussions unfold with growing alarm so far they have taken few concrete steps to resist them.

But no one here doubts that any of these groups, with their bloody histories of fighting the Taliban, could arm themselves quickly if they wished.

“Karzai has begun the ethnic war,” said Mohammed Mohaqeq, a Hazara leader and a former ally of the president. “The future is very dark.”

But even if the editorial board walks the plank it's too late to stop what they started. Al Jazeera has followed the Times' lead (Karzai "holds talks" with Haqqani) and so has the Guardian (Afghanistan in turmoil after peace talk rumours). Even Dawn, Pakistan's major English-language newspaper, jumped into the fray (US aware of Afghan-Pak contacts with Haqqani).

The Guardian reporter scared up the best quote to emerge so far from the mutiny:

Michael Semple, a regional expert, said he was alarmed at the speed with which the [Afghan] political class was fissuring.Rum, anyone?

"Sane people, who've been part of this process all along, are now saying the country won't survive till the end of the year," he said.

********