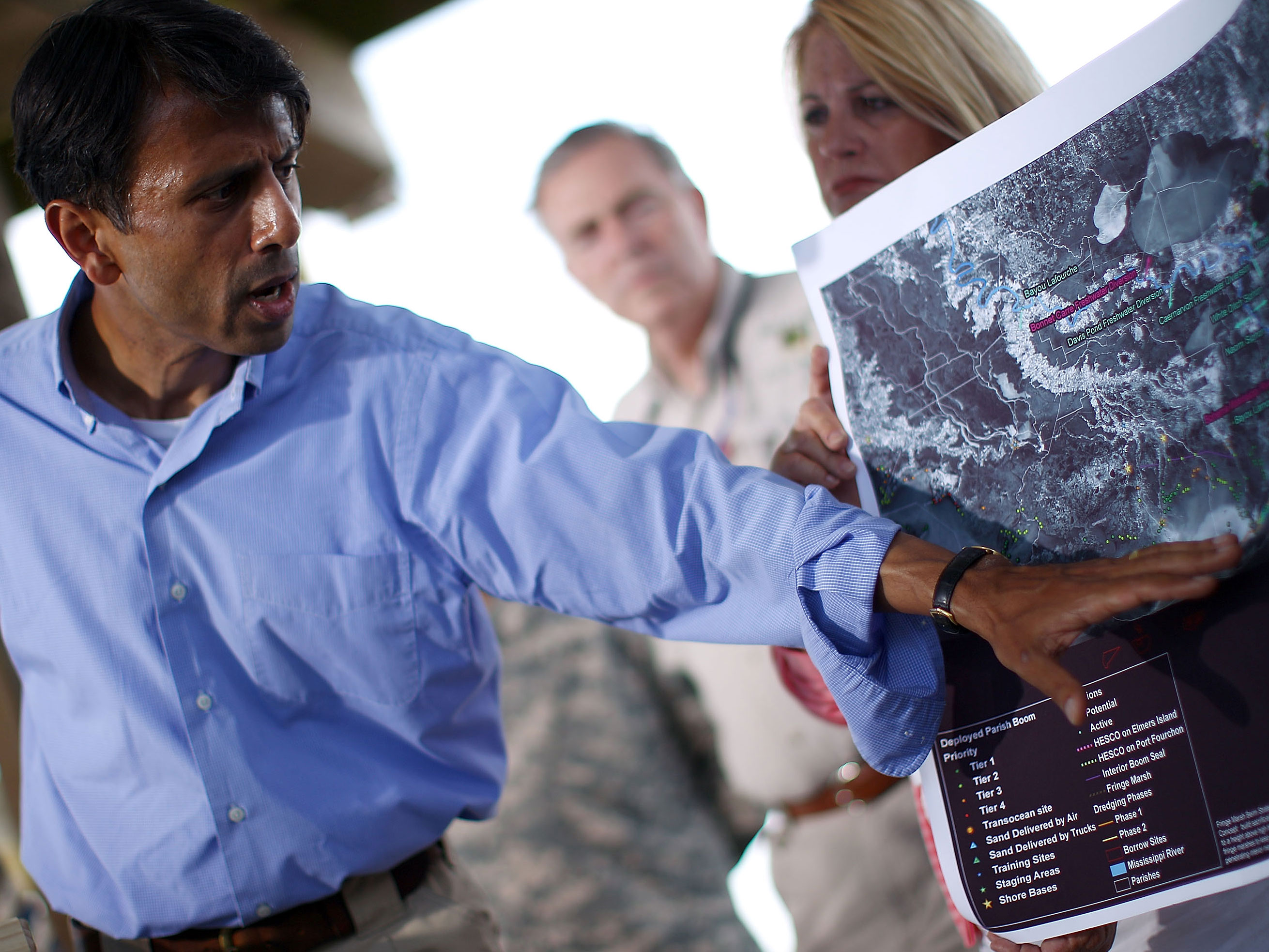

Photograph by Win McNamee/Getty Images

"Let there be no mistake, we are in a fight to protect our way of life." - Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal

"Let there be no mistake, we are in a fight to protect our way of life." - Louisiana Governor Bobby JindalMay 31, 2010, (U.K.) Guardian:

...Experts say the unprecedented depth of the spill, combined with the use of chemicals that broke the oil down before it reached the surface, pose an unknown threat. [1]May 31, 2010, Market Watch:

"It's difficult to marshal resources to do a thorough job of charting what the impacts are," Jeffrey Short, an environmental chemist who worked on the effects of the Exxon Valdez spill, told Nature magazine. "It's especially difficult when weird things happen to catch the scientific community by surprise. That's clearly the case here."

Louisiana, the nearest state to the leaking well, some 42 miles offshore, has been the most impacted. The state's governor, Bobby Jindal, said more than 100 miles of its 400-mile coast had so far been polluted.

State officials have reported sheets of oil soiling wetlands and seeping into marine and bird nurseries, leaving a stain of sticky crude on cane that binds the marshes together. Billy Nungesser, president of Plaquemines parish, said he had seen dying cane and "no life" in parts of Pass-a-Loutre wildlife refuge. ...

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Monday expanded the area of the Gulf of Mexico that is closed to fishing due to a giant oil spill, as states along the Gulf Coast braced for the impact on jobs and their economies."We at the end of the day can't wait. We have to help ourselves"

The federal government has closed all commercial and recreational fishing across nearly 62,000 square miles, or nearly 26% of federal waters in the Gulf, up from about 60,600 square miles closed on Friday, NOAA said.

In Louisiana, which is closest to the spill, officials have shut down many areas off the state's coast to fishing and shrimp and oyster harvesting, although some areas remain open.

While Louisiana officials focused on convincing a concerned American public that Gulf Coast seafood is safe to eat, Florida officials were working to entice people to visit their state, which hasn't been physically affected by the spill.

Louisiana officials on Saturday asked BP for $457 million for a long-term seafood-safety plan, and for an additional $300 million to provide emergency financial assistance for people working in the commercial and recreational fishing industries who have been hurt by the oil spill, the officials said. Louisiana's seafood industries generate about $4 billion a year, the state officials said.

"The future of this industry is in peril," Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Secretary Robert Barham and other officials wrote in a letter to BP Chief Executive Officer Tony Hayward. ...

A drama has been unfolding in Louisiana to save the state's barrier islands, fishing industry, and way of life for those who have fished Louisiana's waters for generations. Governor Bobby Jindal has been leading the charge; he's been ably backed by thousands of volunteers and a host of state officials.

Nobody involved needs to be persuaded of the seriousness of the situation, which in addition to the threat from the oil spill has included stonewalling and/or foot-dragging by federal officials, Coast Guard, Army Corps of Engineers, and BP.

On May 4 the New Orleans newspaper Times-Picayune, which played such a vital role in reporting on Hurricane Katrina's impact on Nola (New Orleans), reported on the marshaling of efforts by local officials, who knew by that time that they couldn't expect much outside help at that crucial stage -- and that they were facing an uphill battle because of powerful oil industry interests. So before I focus on Jindal's efforts I'll quote from the TP report by way of introducing you to some of the cast, which features Democrats and Republicans working in close concert:

Gov. Bobby Jindal praised the efforts of local leaders including St. Tammany Parish President Kevin Davis and New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu to protect Lake Pontchartrain and adjacent areas from possible contamination by the Gulf of Mexico oil spill.Bobby Jindal, the one-man army

U.S. Sen. David Vitter joined Jindal, Davis and Landrieu at a press conference at a spill response command center set up at Fort Pike in eastern New Orleans, across the Rigolets from St. Tammany Parish.

Jindal credited local officials for taking the initiative to put protection plans in place. Davis oversaw the positioning of protective booms near the Rigolets and Chef Pass beginning Saturday, anticipating possible encroachment of the oil spill from the gulf into Lake Borgne and toward Lake Pontchartrain.

Local and state leaders know best what's at stake for the region, and they are formulating effective plans to keep the area save, the governor said.

"We need the Coast Guard to approve these plans," he said. "We need BP to fund these plans.

"We're not waiting for the cavalry. We're going to do everything we can to protect our coast."

BP reported today the first sighting of the oil slick as far as the Chandeleur Islands, the closest position yet to eastern New Orleans and St. Tammany Parish, Jindal said.

Landrieu, who was inaugurated Monday as mayor of New Orleans, said Davis contacted him last week, while he was still serving as Louisiana's lieutenant governor, to ask him to authorize the use of Fort Pike as an incident command center.

"We at the end of the day can't wait," Landrieu said. "We have to help ourselves."

From Jesse Zwick's May 31, 2010 article for The New Republic, Post-Spill Praise For Bobby Jindal

[...] Constantly jumping in and out of National Guard helicopters and drawing up plans for additional "burrito levees" and "boudin bags" needed to stop the oil slick from flowing further into his state's marshes, Jindal has quickly mastered the details of the issue.Staring down the barrel of catastrophe

At a press conference in New Orleans in mid-May, the Washington Post reported that "he gave updates on the size of tar balls washing up in Port Fourchon (up to eight inches), the number of sandbags to be air-dropped (1,200) and state money spent to date ($3.7 million). He also provided a weather forecast ('The winds continue to come out of the southeast, 10 to 15 knots')."

All that knowledge has forced Jindal to admit that his state is facing a huge crisis — one that merits an equally huge state and federal response. This big government position hasn't exactly endeared him to his GOP colleagues (who think he's in league with an alarmist camp of environmental groups that want to villainize Big Oil) or to Democrats (who think his impassioned calls for a greater government response smack of hypocrisy), but Jindal has displayed the kind of smarts and ideological flexibility that we should applaud in our leaders, no matter the party.

The first thing Jindal did right was acknowledge the scope of the catastrophe. This might not seem deserving of praise — until one looks at how other Republicans have reacted. Nervous about a populist backlash against offshore drilling, or even growing momentum for a climate bill — and contemptuous of environmental science in general — many Republicans have downplayed the disaster.

For example, Jindal's gulf state GOP colleague, [Mississippi Governor] Haley Barbour, was quick to urge tourists not to cancel their trips to Mississippi's beach towns, comparing the deluge of crude to the sheen of gasoline from a motor boat.

"We don't wash our face in it, but it doesn't stop us from jumping off the boat to ski," he told the AP.

And Barbour's not alone in taking such a blasé stance. "Haley has actually taken the smarter approach, from a national perspective," a GOP operative explained to Politico yesterday. "He has taken the long view, that this shouldn't kill an important source of energy."

Rather than maintain such political orthodoxy, Jindal has been wise to stand up for his state and talk about the spill for what it is: "This oil threatens not only our coast and our wetlands; this oil fundamentally threatens our way of life here in south Louisiana." [...]

The true "long view" is that the BP oil disaster is threatening the world's 29th largest economy, which is what the Gulf region is.

As for offshore oil drilling, Jindal has always been a strong proponent and I assume he remains so. One doesn't need to be a member of the Green Party to take aim at gross negligence on the part of BP and what is arguably collusion between the oil giant and the federal government. At the least the feds wimped out in their dealings with BP.

Zwick's article is a little behind events when it talks about the disagreement between Thad Allen and Jindal regarding the sand berms but before I plunge into that part of the story, readers who're trying to play catch-up with the oil disaster need to realize that the debate about the berms is a major issue. Here's why:

The 'barrier islands' dotting the Gulf coast are the only defense against the worst from hurricane winds once they hit land, and the entire Gulf coast region is hurricane alley. The islands and their vegetation brake the winds, draining off some of their fury before they make major landfall.

For various reasons, which add up to bad land management across decades, the islands, some of them so tiny they just qualify as 'marshes,' have been severely degraded. That means damage to the coastal areas from even less than catastrophic hurricanes has become worse as time has gone on. Just the mobilization effort in anticipation of the hurricanes is very expensive not to mention the cleanup from hurricane damage.

Meanwhile, a huge fishing industry grew in the Gulf coastal areas, and the Cajun-Creole cultures in southern Louisiana are greatly dependent on it. They took a bad hit from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 but they came back; as one fisherman said, "That was just wind and rain." Now, with the BP oil disaster, they're looking at the possibility that their way of life is coming to an end.

At the same time Gulf oyster and shrimp fishing became an industry U.S. oil refineries perched themselves along the Gulf shore. Add tourism to this, and that's why the region is the 29th largest economy in the world.

Governor Jindal is not only standing up for an American state but also for an entire region that is an important part of the world economy. He's also standing up for the unique culture in Louisiana, which is an important part of the American heritage.

So, those humble little pieces of land near the US coast are crucial and that's why Jindal and other Louisiana officials are knocking themselves out to save them.

Of booms and parishes

Before I return to sand berms, a few terms of art for readers who plan to follow the drama:

1) Boom: "A floating device used to contain oil on a body of water. Once the boom has been inflated, it is towed downwind of the oil slick and formed into a U-shape; under the influence of wind, the oil becomes trapped within the boom."

The oil can then be skimmed or sucked from within the boom. I don't know the exact material used in the booms; probably heavy plastic or somesuch. They look like giant sausages strung together when they're inflated.

Why sand berms, then, if the artificial booms work? They need calm waters or they get washed away. That's what happened when Alabama Governor Bob Riley tried to use them, in conjunction with gates, to keep oil out of Mobile Bay. The strong current washed them away. As to why he didn't think of that before trying the experiment -- from a May 28 New York Times piece on how the governors of five coastal states have been dealing with the oil spill threat:

...Casi Callaway, the executive director of Mobile Baykeeper, an environmental group, said she could have told him that would happen - if she and others with coastal expertise had been consulted. But they have had a difficult time getting through to the decision makers, she said.My question is whether the sand berms hold up in hurricane-force winds. I guess Jindal will have to deal with that problem if he comes to it. Right now it's a race against time -- a race against the looming hurricane season, which started a day or so ago, and the spreading oil spill.

2) Bayou (French or Choctaw Indian word): "A body of water typically found in flat, low-lying areas, and can either refer to an extremely slow-moving stream or river (often with a poorly defined shoreline), or to a marshy lake or wetland. Bayous are commonly found in the Gulf Coast region of the southern United States, particularly the Mississippi River region, with the state of Louisiana being famous for them."

3) Parish: You'll come across the term frequently in news from Louisiana. Basically a parish is a county in Louisiana, of which the state has 64; the old name was retained as a tradition. Louisiana is a melding of French and Spanish colonies, which were Roman Catholic. From the Wikipedia article on the parishes:

Local government was based upon parishes, as the local ecclesiastical division (French: paroisse or Spanish: parroquia). Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Territorial Legislative Council divided the Territory of Orleans (the predecessor of Louisiana state) into twelve counties. The borders of these counties were poorly defined, but they roughly coincided with the colonial parishes, and hence used the same names.See the article for more detail on the parishes and their various forms of modern-day administration.

4) Hesco baskets: At this point I refuse to get that far into the weeds of oil spill cleanup equipment so I have no idea what they are. Ditto for burrito levees and boudin bags.

5) There's a huge body of information on the internet about barrier islands and their importance but for a primer Wikipedia's article is a good start.

Jindal vs Allen

Now to return to Zwick's report. Note that the tussle between Jindal and Allen is also a window on the federal government's dealings with the states.

The administration's point man for the crisis, Coast Guard Commandant Admiral Thad W. Allen, argues that they're fulfilling all the demands outlined within the plan agreed upon by the gulf state governors, and that they'll get to Jindal's additional requests next.The Louisiana Governor's office has a different take. From the May 28 press release:

Allen also takes issue with Jindal's claim that his sand-island scheme could begin working within 10 days of approval, arguing that construction would take closer to nine months. Then there's the legitimate question of whether it'd even work: "For the cost involved, the chances of being successful at doing any good … are minuscule," speculated Jerome Milgram, a professor at MIT.

... “We spent much of our time with [President Obama] today discussing the importance of our sand-boom [berm] plan in the fight to protect our coast against the millions of gallons of oil that continue to hit our shores.As to the environmental risk that the sand berms might pose to the marshes, Gov. Jindal has the answer for that too. From Bill Capo's May 27 report for Louisiana's WWL-TV:

Just yesterday, we visited the state-directed dredge at East Grande Terre near Grand Isle that we refocused to create sand-boom under our plan. On our own, we already took the dredging permit the state had control over and switched the project over to build sand booms as part of our coastal protection plan.

This state-directed project at East Grande Terre is about a 2.5-mile project where work on our sand boom plan began last week. The Coast Guard told us yesterday – after weeks of reviewing our plan that they approved a single segment of just two miles to see if the sand-boom works. This is another example of too little too late.

“We expressed this frustration to the President and he agreed that work on the first segment must begin immediately and that within two to three days they would review whether the sand boom will stop oil and make a decision about whether or not they will force BP to pay for the other five segments of the plan the Army Corps of Engineers already approved.

“We know sand boom works, we have seen it work in Thunder Bayou and Elmer’s Island, but if the federal government needs to see it work, they need to do that quickly. We don’t want the federal government creating excuses for BP. This is BP’s oil spill. They are the responsible party but we need the federal government to hold them accountable and make them responsible. We are fighting to help protect our coast under this sand-boom plan, and as of today more than 107 miles of our coast have already been impacted by oil.

We know this oil will continue to hit our coast again and again. We have to put multiple protection measures in place. We continue to ask federal officials to approve our entire sand-boom plan from the northern Chandeleurs to the Isle Dernieres chain. Our entire coast is important. ...

... Jindal also took to the air to see how the dredged barriers being put out to protect the state are faring. The state began the project even before getting the go-ahead from the Coast Guard Thursday.The Jindal-Nungesser tag team

The dredged area is two to three miles off the coast. The machines suck up the sand in that area and pump it onto the beach.

“It dredges sand off the floor of the Gulf, that gets piped in here, and the graters work from the center of the island off in both directions,” explained Jindal. “They’ll build it up to five to six feet high and two and a half to three miles wide.”

They’re restoring 127 acres of beach and building it up to six feet high. During the trip Jindal learned that the first segment of his 24-segment, long sought dredging plan had been approved.

“It’s better than still waiting for an answer,” said Jindal of the news. “If we had gotten approval when we first asked for it, we could have built ten miles by now.”

Jindal had an answer for those who say the barrier islands would keep needed water from getting to the marshes.

“We’re not proposing to build a continuous barrier,” he said. “We know that’s not practical. So we would allow the normal tidal currents to move in; what that allows the Corps, the Coast Guard and BP to do then is to focus their booming and their skimming and resources on a few cuts in a few passes.”

The dredging on Grand Terre started last year as a coastal restoration project but it has been turned into a project to protect the beach from the spill’s effects and Jindal hopes that Obama can see the benefit first hand on his visit Friday.

“By law BP is the responsible party for this disaster but we need the government to make sure they actually are a responsible party and fulfill their obligations.”

By helicopter Jindal inspected the multiple layers of defense being used to protect against the oil, including land bridges by the National Guard to stop the pollution, large sand bags, lines of boom and barriers of Hesco baskets. ...

According to a report by Arian Campo-Flores for the May 27 edition of Newsweek, it's actually Billy Nungesser, the President of Plaquemines Parish, who came up with the sand berm idea:

...In recent weeks, Nungesser and Jindal have been relentlessly pushing a new plan: to fortify barrier islands with dredged sand so that the oil has a harder time making it into the marshes. The $350 million project —which Nungesser is credited with coming up with — has intuitive appeal, and indeed, restoring those protective buffers has long been a priority for environmentalists.1) See this May 31 article at Times-Picayune about the dispersants and underwater plume sightings; also see the blog by Samantha Joye, one of the UGA Marine Department scientists inspecting the underwater plume, who is quoted in the article:

Yet some scientists have raised questions about the scope of the plan. For instance, Gregory Stone, director of the Coastal Studies Institute at Louisiana State University, says it’s unadvisable “to embark on a project of this magnitude without having at least some semblance of what might actually result.”

The Army Corps of Engineers apparently has reservations as well, since so far, it has refused to grant the necessary emergency permit. Yet Nungesser and Jindal insist that their idea could save some of the marshes. And, they argue, if the federal government doesn’t like their proposal, then it should come up with an alternative—something much more aggressive than simply laying down boom.

In the past week, Nungesser and Jindal have stepped up their rhetoric against BP and the federal government, especially the Coast Guard. “We have been frustrated with the disjointed effort to date that has too often meant too little too late to stop the oil from hitting our coast,” Jindal said at a press conference on May 24.

Nungesser, for his part, has made a daily sport of lashing out at Admiral Thad Allen of the Coast Guard, calling him “an embarrassment” and “a cartoon character.” (Today, the Coast Guard approved portions of the sand-berm plan).

On Wednesday, the pair were at it again. Joined by James Carville and Mary Matalin, Jindal and Nungesser toured South Pass at the mouth of the Mississippi, heading an entourage of boats carrying wildlife officials and media.

As a storm rumbled in the distance, a few shrimpers glided past. Jindal’s and Nungesser’s boat pulled up to patches of roseau cane that were stained dark brown by oil at their base.

“Everything was dead in the marsh,” Nungesser told me afterward. “I get tears in my eyes, because when you’d pull into that marsh previously, fish would jump and scurry.” Now, “ain’t a bird, ain’t a bug, nothing.”

Worse yet, there was no sign of activity to clean up the muck or defend against the invading slick. “There was nobody out there doing anything,” said Nungesser. “It was disgusting.”

http://gulfblog.uga.edu/

No comments:

Post a Comment