For the latest on the NATO-Russia crisis view the sources in my post from last night.

The motivational speaker Les Brown once advised to interpret a lot of turbulence in your life as a sign that you're trying to move rapidly to a higher level, in the way jet plane passengers feel air turbulence if the plane rapidly gains altitude.

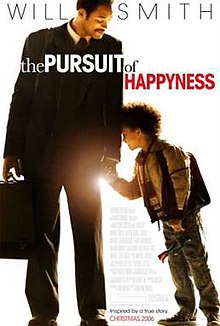

Years later The Pursuit of Happyness (2006) was like a coda to his words. I found the film, based on the true story of a black American salesman named Chris Gardner, almost unbearable in parts and at one point I did stop watching, saying, "I can't deal with this." But a moment later I gritted my teeth and I'm glad I did.

Eventually, it starts to come clear that while everything that could go wrong for this man did, much of it was that he'd been able to put off dealing with time-consuming personal problems. Then they all came knocking again, at just the time he was homeless with a small child in tow and trying to find a new direction in his career.

He eventually became a millionaire, to be a plot spoiler, which I'm doing as a kindness to other sensitive movie viewers. Yet even knowing this it is still hard to watch. The story becomes bearable when it's clear he realizes that no matter what hell he was going through, he had to make time to deal with the old problems as they came back to haunt him.

To get intellectual about it, he had developed a pattern of avoidance -- a fairly common survival stratagem. He was okay as long as he was on a routine path. Once he faced big unknowns the worst price for avoidance came due. So while he was hit with bad breaks he was also meeting head-on a pattern of his own making. To endure the turbulence he had undo the pattern.

This is what I'd call working to improve one's character at the point of a gun.

Of course a person isn't a nation much less a collection of ones, yet I recalled Chris Gardner's story yesterday when I read the following passages from Richard Sakwa's The Deep Roots of the Ukraine Crisis: We must rethink the post–Cold War security order. (Initially published April 15 for the May 4 edition of The Nation.):

On July 6, 1989, in an address to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, France, Gorbachev outlined his ideas for a “Common European Home.” This vision, now commonly referred to as “Greater Europe,” laid out a program for geopolitical and normative pluralism in post–Cold War Europe. Gorbachev argued eloquently and forcefully that different systems could coexist peacefully.

Gorbachev was calling for the transcendence of Yalta, a position he would assert at the Malta Summit later that year. In Strasbourg, he called for a new dynamic in European international relations that would encompass the interests of powers both great and small. This would be a multipolar Europe with space for experimentation and diversity.

The tragedy of the Malta Summit is that Gorbachev was not talking about these ideas with European leaders, but with the president of the United States.

Unlike at Yalta, there was no Winston Churchill to speak on behalf of Europe. Not surprisingly, the idea of a Greater Europe was the last thing that Bush wished to talk about, since it would signal precisely what America had long feared: a split between the European and American wings of the Atlantic alliance.I'd recommend you read the whole thing. Yet Sakwa is giving Europeans a pass they had stopped meriting by the end of the Soviet Union. From that point on the Europeans became masters at avoiding responsibility for their own security. They would have 1,000 excuses for doing this but it boils down to "Because they could."

The upshot was that they stayed with an ocean-spanning defense alliance rather than build their own alliance, one that should have included Russia.

The price for the pattern of avoidance? Maybe I'll contemplate the question later today over a plate of dim sum.

No comments:

Post a Comment